Building a home without plastic

GreenSquareAccord has built Europe’s first plastic-free affordable housing development. Peter Apps finds out how the association did it and what lessons the sector can learn

The journey towards building the first plastic-free home in Europe, and possibly the world, began in a traffic jam.

A closure to the M5 motorway in the West Midlands required the senior management team at housing association GreenSquareAccord to sit in traffic every morning as they made their way to the 25,000-home landlord’s head office. This meant driving slowly past an advert placed by the Marine Conservation Society.

“The senior management and myself were spending an inordinate amount of time in a traffic jam, looking at an image of turtles and sea life trapped in bits of plastic,” says Carl Taylor, assistant director of new business at GreenSquareAccord.

The housing association was already invested in the idea of sustainable housing. One of its legacy organisations, Accord, owned a factory – which now belongs to the merged organisation – that produced lightweight timber frames and the landlord had used them to build carbon-neutral homes in Marfield. But the poster presented a new challenge to the team: low-carbon development was one thing, but what about all the plastic that went into every new build the association turned out?

“It occurred to us that while we were producing what should be seen as really high-quality, low-carbon housing, we weren’t necessarily producing the most sustainable housing and that we should try and do something to use more natural materials and to remove plastic where we could from a development,” Mr Taylor explains.

GreenSquareAccord was able to secure £850,000 from an Interreg project called CHARM (Circular Housing Asset Renovation & Management), which was using EU money to fund housing projects across Europe to demonstrate methods to make housing development more circular. This means using less material that could not be reused and may end up in landfill or an incinerator at the end of its life.

The association match-funded the remainder of the cost of the development, which is a block of 12 one-bedroom flats, from its own resources. Each home will be for affordable rent.

Stripping away the plastic

The project began from first principles. GreenSquareAccord’s design team was shut in a “dark room” and challenged to strip away as much plastic from the design as possible.

Some of the changes were obvious: the kitchen units are all solid timber, as are the doors; the bathroom utilities are all ceramic, wood and metal; the floors are traditional linoleum rather than vinyl; and the carpets are made from sisal (a material woven from agave plants). All of these represent relatively straight-forward trade-ups from a commonly used cheaper option to a more expensive but widely available plastic-free material.

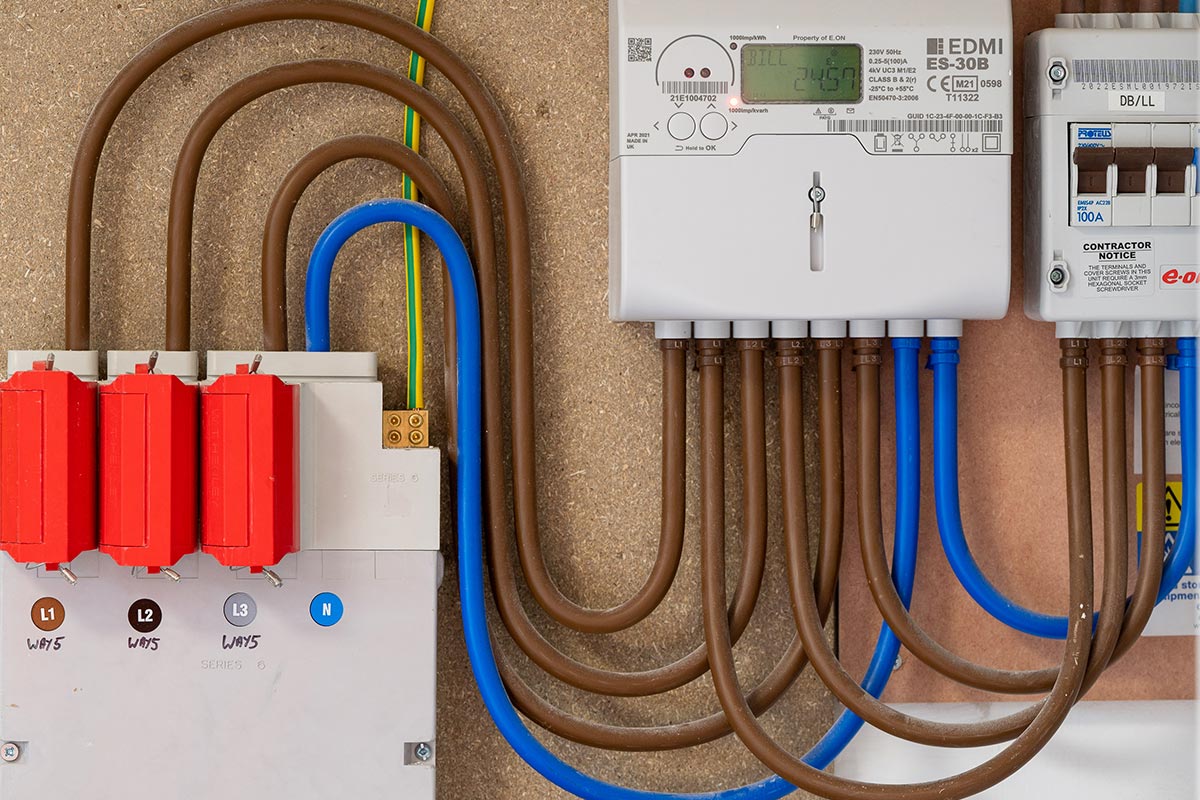

Where things became slightly more complex is the electrics. The development has no plastic cables. Instead, the wires are mineral-insulated, copper-clad cable – something that is now typically used in nuclear submarines and power plants, but was previously widely used in high-rise buildings. This created the need for specialist electricians.

“It took a bit of research for us to get there; that was a big, big change,” says Mr Taylor. “Our subcontractor had got the guys, but they hadn’t done it for about 15 years. So we had these two old guys who trundled round the building installing it.”

Not everything could be plastic free, though. The sockets and junction boxes are the same plastic that you would see in any other home. The meter boxes also contain plastic, as do the development’s smoke alarms, fire alarms and intumescent strips used for fire stopping.

“There are regulated areas, and areas which relate to safety where we just couldn’t compromise or change,” explains Mr Taylor.

Nonetheless, the automatic opening vent – which will help smoke leave the building in a fire – has been developed to be plastic free, which is unusual.

Timber frame developments such as this one carry a higher fire risk than masonry structures. Several large blazes have seen properties destroyed if fire is able to attack the frame of the building, meaning it burns inside the walls and is close to impossible for the fire service to extinguish.

This is mitigated here at this development because the panels are put together at a factory, which enables greater control over the workmanship issues that can plague traditional sites. There is also an innovative design where the walls have three skins of plasterboard, meaning it will not be immediately compromised by drilled holes or damage.

The block is also fitted with a manually operated communal fire alarm – an unusual feature in a general needs building. The exterior cladding is non-combustible cementitious board and the balconies are solid metal rather than timber.

“We’re very aware of the regulatory changes since Grenfell, and there are certain things the warranty providers have insisted on,” says Mr Taylor.

Piping, which would normally have been push-fit plastic, is metal. This is one of several areas where the changes have resulted in an increase in quality. “It’s an open secret in the construction industry that plastic piping leaks everywhere. And it’s a constant issue around quality and a very high maintenance cost,” explains Mr Taylor.

“This is a work of art,” he adds, proudly opening a service cupboard and displaying a tangle of copper and steel pipework. “This is a nice solid steel soil stack, which takes all the waste out of the building. It really is a thing of beauty.”

The heating system is solar thermal. Solar panels on the roof heat water in a metal tank, which is then distributed around the property by copper pipes. “It’s all copper and really high quality,” explains Mr Taylor. “What we’ve noticed is by changing the plastic, we’ve really upped the quality.”

The insulation between compartments is glass wool, meaning the building is free of any of the combustible plastic foams that have caused such concern in the industry since being used on Grenfell Tower.

Some of these changes add more weight to the building, but the timber frame has been designed accordingly to take account of the additional load.

Other features have been removed entirely. Most blocks of flats have an intercom system with the front door, but this has been replaced with an app which tenants will control with their smart phones. Tenants will also get a metal rather than plastic fob to enter the building.

Construction challenges

The construction process also threw up some challenges. “A big, big issue for us was sealant,” says Mr Taylor. “It was very difficult to find a sealant that was plastic free. We think there’s just one sealant in the world that is plastic free, and the construction team have been going nuts at us because we made them use it for the kitchen, for the windows, for everywhere.”

Even the paint is plastic free; it is made from a mix of graphene and lime. Mr Taylor says there has been recent research which showed that paint is a major contributor to microplastics – the small particles of plastic which work their way into the food chain.

How much of this is relevant, though, to its original marine inspiration? We can all see how disposable plastic bags or beer rings might end up around the neck of a turtle, but surely we do not throw away houses.

Mr Taylor disagrees. “Are you old enough to know what I mean by Trigger’s broom?” he asks your correspondent – somewhat generously.

Trigger, for the benefit of those under 30, was a street sweeper in the 1980s sitcom Only Fools and Horses, who memorably boasted of having had the same broom for 20 years. When challenged, he explained that it had 17 new heads and 14 new handles during that time.

“A house is the same,” Mr Taylor explains. “When a kitchen unit gets scrapped, it ends up in landfill. The central heating system will last for eight years. The bathroom – 22 years. The electrics – 18 years, maybe.

So in the lifetime, while the house stays there, everything inside it gets changed fairly frequently. And when it does, it ends up in landfill because that’s the nature of how the industry works.”

All of this work has added cost. The project has cost around £800 per square metre more than a traditional build. This is something that is viable with the EU grant, but would not be on a scheme that has been funded more traditionally. And some of these costs would be higher today, with metal prices soaring.

There are savings to be had over time. The kitchen, bathrooms and pipes will last longer, and there will be lower maintenance costs. However, this is very much a project which demonstrates alternatives rather than one which will be directly used elsewhere. But this may change.

“We think this is ahead of its time,” says Mr Taylor. “We see what’s happened to fuel prices. Plastic is a by-product of fuel. As the world warms, we won’t be able to burn fuel as we want and people will look for plastic-free alternatives. This was a step to see how far we could go and what lessons we could learn. Our mainstream developments will take lessons from this.”

As we move to a more sustainable future, we will all have to reduce our reliance on the plastic which is such an ubiquitous part of our lives. The housebuilding industry is no different, and this project points a way forward.

“We want people to learn from this,” states Mr Taylor. “You don’t expect people to suddenly say, ‘Let’s build everything plastic free’, because it’s not that simple. But we’ve achieved this now, it’s here for people to come and look at and learn from and think about what we could change.”

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.